COACH’S CORNER - Pacing an Ultra by Andy DuBois

Andy dubois explains how good pacing in an ultra is important to achieving your potential

Good pacing in an ultra is critical to achieving your potential on race day yet few of us really understand how an ultra should be paced. We can spend ages working out to the nearest second or two per km how to run a marathon but in a ultra many of us just start running and see how we feel on the day.

At best one might look at a pacing chart created by a data loving ultra runner for a particular race but these are NOT pacing charts. They are charts showing estimated times to get to various checkpoints based on ones estimated finish time. They can be useful for planning nutrition and hydration demands and to give ones crew an estimated time you will be at checkpoints but they cant be used for pacing.

The reason for that is they don’t give you any information that allows you to speed up or down at any particular moment during the race. Yes they can tell you if you arrived at a checkpoint sooner or later than targeted but you cant use that to pace oneself. For these reasons:

- The checkpoint times are based on your target finish time hence you need an accurate target finish time - one thats based on your actual fitness not what you hope you might do.

- The accuracy in determining the checkpoint times even if you have a very good estimated finish time is determined by other runners ie these charts take data from other runners that have run your target time in previous races and then use the splits of these runners to determine projected times at the checkpoints. How well they paced it is unknown. Even if the creator of the pace chart only takes data from runners that seem to have paced it well it cant take into account your relative strengths and weaknesses on the course .

- If you arrive at a checkpoint behind time do you try and speed up? If you arrive ahead of projected time do you slow down? There are no easy answers to these questions. If you arrive behind time maybe your estimated time was too ambitious or maybe you are pacing it really well and will make up time in the second half due to being more conservative in the first half. If you arrived ahead of time maybe you have gone out too hard and will blow up later on. Lots of unknowns with no easy way to determine the truth.

- The main one above all else is checkpoint charts don’t allow you to look at your watch at any moment on the trail and decide if to run faster or slower.

So how do we pace an ultra?

Pacing an ultra is far more difficult than pacing a marathon or shorter distance race. There are two main reasons for this.

- Marathon and shorter distance races can be run with even spits - as we will see later optimal ultra pacing is quite different.

- Terrain in trail ultras means the pace varies enormously.

What does the research say?

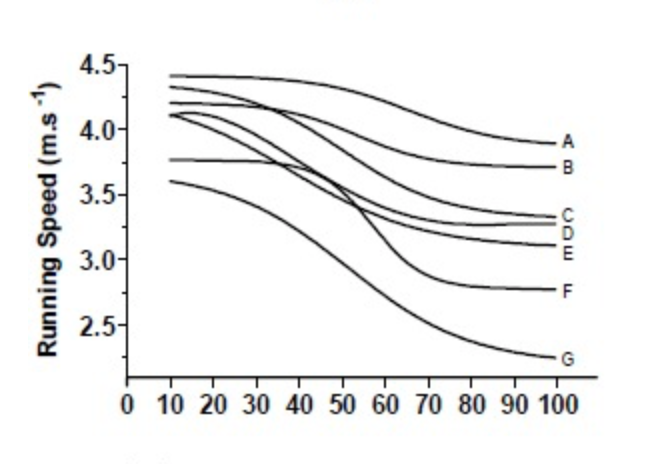

In a study by Lambert et al “Changes in Running Speeds in a 100 KM Ultra-Marathon Race “ they looked at 100km road runners in the world championships and found that the top runners slowed down 15% compared to their initial starting speed with the slower runners slowing down significantly more.

The study grouped finishers into groups of 10 ( A to G) according to their finish time.The drop off in speed in the slower runners is significantly more than the faster runners.

What about in 100 mile flat races ?

Here is a strava plot of Zach Bitters 100 mile US record. Just as in the 100km you can see a drop in pace occur – in this case around 75 miles.

What about in 24 hour races ?

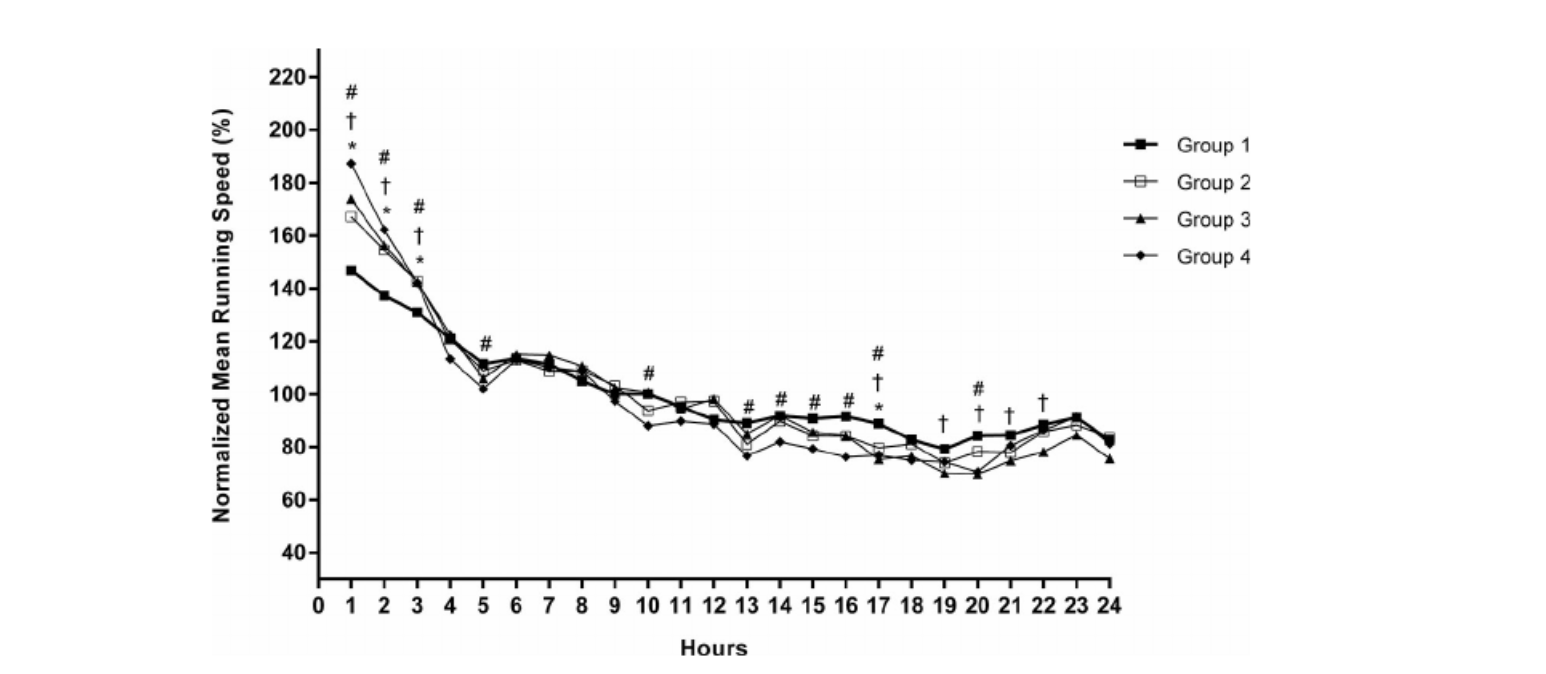

A study by Bossi et al entitled “Pacing Strategy During 24-Hour Ultramarathon-Distance Running” looked at exactly that and concluded, “…. fastest runners start at lower relative intensities and display a more even pacing strategy than slower runners.”

The graph below shows the normalised mean running speed to allow comparison between groups.

Group 1 which started with the slowest relative speed ended with most distance; 180.5km, Group 2 ran 142.4km, Group 3; 122.1km and Group 4; 97.2km. [NOTE Group 1 didn’t start at the slowest speed – but their speed was closest to their overall speed than the others- the other 3 groups started much faster relative to their mean running speed over the 24 hours.]

It looks like we all get slower but the faster finishers slow down less and also start at a pace that is relatively easier for them than the slower runners.

The take-home – start easy and slow down as little as possible. But how easy is easy?

Does the same apply in trail ultras?

Until recently it has been impossible to determine objective pacing strategies for trail races due to the constantly changing speeds that a trail forces you to make. With the advent of power meters, we can now measure power throughout a race and power can be determined independently of the terrain – ie the speed you end up running at say 200 Watts will vary depending on the terrain but the effort remains the same.

I’ve had quite a few runners use power meters in races over many years which has allowed me to see what has worked best in terms of pacing. Note although I’ll be discussing power you don’t have to have a power meter to benefit from this discussion – we are looking at pacing and I’ll relate back to running without power meters later so bear with me

Let’s have a look at some runners that had good races to see what the reduction in power looks like.

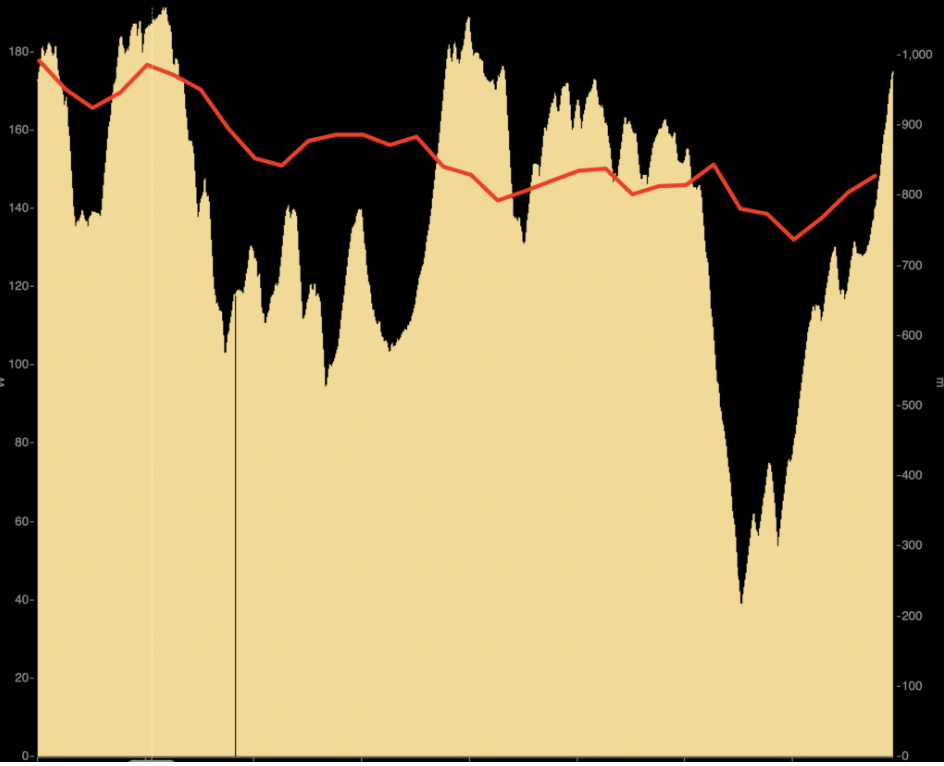

Here is what it takes to run 9.24 at the UTA 100. The red line represents run power.

From start to finish there is a reduction of 15% which corresponds exactly to what the study on 100km road runners found.

Below is another runner who had a great race, running just over 15 hours in the UTA100 with a reduction in power of 16%.

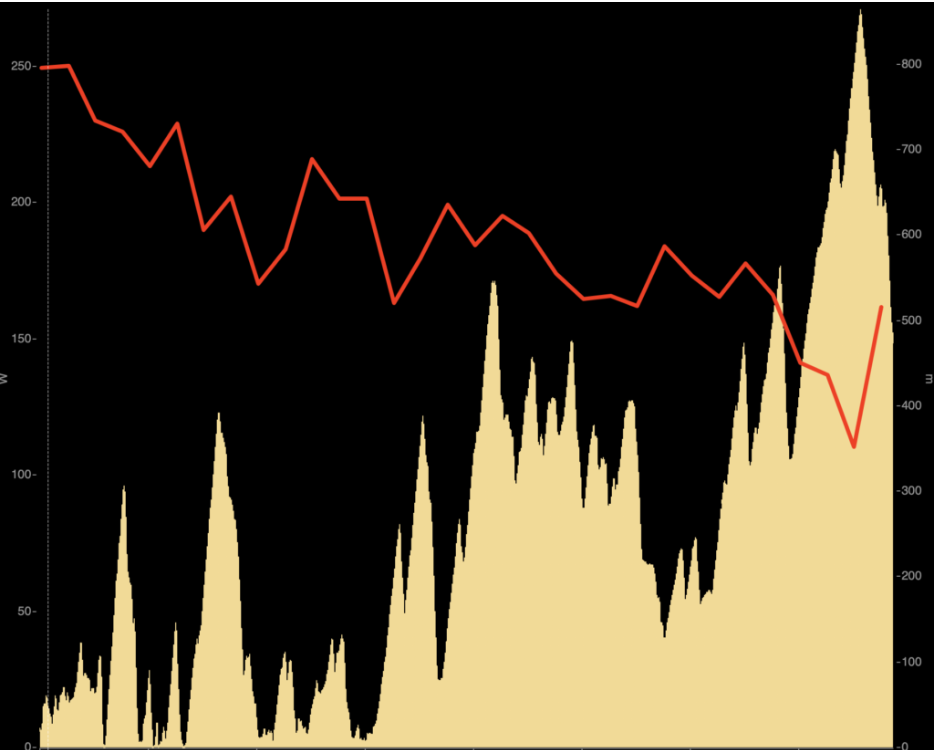

What about when a race doesn’t go so well?

In this race, at the HK100, the runner lost 35% of initial power and finished well behind expectations.

What does all that tell us other than to have a good race you shouldn’t slow down that much – which of course is obvious?

What about those athletes that finish strong, catching athletes in the back half of a race? Do they speed up?

Below is Sunmaya Budhas power data when she stormed home to almost snatch the win in the 2022 UTMB-CCC race running the second fastest time in history. She lost 13% of her initial power.

So even when making up time on the race leader (who set a course record) she still slowed down.

Another advantage of power is we can look at what intensity the athletes started at and determine at what power level leads to the least reduction in power and therefore fastest possible finish time.

Let’s revisit each of the athletes above and talk about intensity.

The 9.24 UTA runner ran his long runs leading into the race at around 225-235W . His starting power was 6-10% higher than long run power.

The 15 hour UTA runner started at 178W and her longest training runs were around 165-175W . She started 3-7% faster than long run pace.

The last athlete who didn’t have a good race in the HK100, started at 250W and his long runs were around 215-220W ie 12-14% faster.

For those that understand the concept of Functional Threshold (FTP) power or Critical power (CP) the starting percentages were as follows:

- 9.24 UTA – 79%

- 15 hour UTA- 84%

- HK100 - 90%

- Sunmayas CCC – 83%

The higher the percentage of threshold you start the more slow down there is (which when you think about it makes perfect sense – if you start a 100km at say 10km pace you are going to see a much bigger slow down than if you started it at marathon pace). The data suggests that for a 100km trail race starting at 80-85% of threshold yields the best results for races lasting 10-15 hours. For longer races it will be less than that , for 15-20 hour races 75-80% and for even longer closer to 70%. For those that don’t use power think of it as a percentage of your threshold i.e. hardest pace you can maintain for approx 45-60 minutes and your long run pace is 75-80% of that pace/effort.

What does that all mean in terms of paces?

Let’s use 6 min per k as a benchmark to see what the above actually looks like.

If your long run speed was typically 6 min ks on the flats then I suggest you start at most between 3-5% faster ( unless you are elite in which case can start 6-10% faster ). That equates to 5:42-5:49 minutes per k pace.

A 15 % reduction of that pace means by the end of the race you should be running at approx 6:36 pace.

I’m confused by all the numbers – what does all that mean?

If you are front to mid pack 100km runner start a fraction faster than your long run pace. If you are more mid to back of the pack start same or even a little slower than long run pace. For longer races longer than 100km start a little slower again.

Now that sounds easy but there are a few problems in the execution of that strategy.

With fresh legs running 5:45 min ks min ks feels very very slow ( if you were running flats at 6min ks in long training runs ). Add in adrenalin, competition and all of a sudden you are running sub 5:30 pace and feeling great . Until of course it all catches up with you and your pace drops to well over 7 min ks. You ask yourself why the legs won’t allow you to run any faster when the initial pace felt so easy. The answer is the initial pace wasn’t easy relative to the distance.

The advice to find a pace that feels easy at the start and then slow down a little more is sound advice if you don’t have access to a power meter to give you more objective data.

How to pace the last half of an ultra

Pacing the last half is easy. If you have paced the first half well then it’s just a matter of trying to keep the pace up as much as possible but accepting it will gradually slow down. The perceived effort in trying to minimise that slow down will rise as the race continues.

Should you hike or run uphill?

With power it’s easy – if you can’t run uphill below your power target then hike. Without power, you need to use perceived effort. I see way too many runners pushing too hard uphill and then needing a period of recovery afterward to recover from the effort of climbing. During that period they lose any advantaged gained from pushing harder uphill. When you get to the top of a hill you should be able to resume running either on the flat or downhill at your usual pace without any recovery period. If you were running a flat race you would aim for even effort but for some reason when it comes to hilly races people think it’s ok to push a bit harder uphill as they can recover on the downhill. In almost all cases you’ll lose more time on the downhill recovering than you gained on the uphill.

So if you feel your effort level rising as you climb then slow down. If you cant run up the hill with the same effort as you were running on the flat then switch to a hike.

What about downhills?

Running downhills will usually feel a little easier cardiovascular wise but your heart and lungs aren’t usually the limiting factor in the latter stages of an ultra, your legs are. So downhills should be approached with the idea of minimising the load on your quads. That doesn’t necessarily mean slowly – sometimes the braking forces needed to run slowly downhill are higher than running a little faster, allowing gravity to help and using high cadence short strides to minimise quad damage.

Other factors that affect pacing

Training The above assumes you have trained sufficiently for the race, it assumes you have got a few 4+ hour long runs in and have had consistent weekly training for a number of months, if you are going in underdone then you’ll need to go even slower at the start – ie slower than usual long run pace.

Specificity of training If your training hasn’t been that specific – eg you haven’t done many stairs or hills for a race that has lots of stairs or hills then again your starting pace will have to be slower to allow for the greater fatigue that will occur due to the unfamiliar nature of the course.

Weather If it’s hot and or humid you’ll need to start slower again ( unless your training has been in same conditions as the race and you are acclimatised).

Nutrition Unless you provide your muscles with enough fuel then the best pacing strategy in the world is not going to help. What we often see is if you go out too fast you are more likely to have nutrition issues as the faster pace makes it harder for your stomach to digest what you are putting into it.

Cramp The data I have seen over the last 7 years of looking at power data shows that if you start at the correct intensity then issues with cramp are very unlikely . In almost all cases when athletes have suffered badly with cramp it can be traced back to starting too fast.

Altitude Higher elevations mean you will need to reduce pace especially if unacclimatised.

Can you use Heart rate to pace with?

There are a number of problems with heart rate as far as pacing in ultras.

- Wrist based heart rate can be very unreliable

- Heart rate is slow to respond to changes of pace/ effort

- Heart rate affected by hydration status , temperature , humidity , time of day , caffeine intake

- Have a look at the chart below - does heart rate look like a useable metric to guide intensity by?

Summary

- Pacing an ultra optimally means starting conservatively and minimising the slow down to 10-15%.

- Using a power meter allows some objective data to help pacing.

- One should start ultras at intensities around 75-85% of threshold pace/heart rate / power.

- Without a power metre some practice in running long run pace on fresh legs may help dial in the right pace on race day but in general start slower than you think you should.

Andy dubois has more than 20 years of experience in coaching, is a level 3 aura coach and director of mile 27 endurance coaching, specialising in coaching ultra runners all over the world from elite to back-of-the-pack. iF YOU WOULD LIKE MORE INFORMATION ON BEING TRAINED BY andy, CLICK THROUGH HERE TO OUR AURA ENDORSED COACHES PAGE.